fredrik

What would you say that you work with?

I’m very much as a furniture designer, but working in a, I don’t know, elastic field somehow.

How did you land on furniture?

It was never a conscious decision, it just, like, happened. I randomly ended up at a cabinet making school after graduating from high school. I never planned on being a designer.

how did you end up going in that direction?

I was, like, always into environments, like habitats or something like that. At the same time I was, like, super interested in sleaze culture at large when I was growing up.

Can you define sleaze culture?

I love, like, comics, horror movies, sci-fi. I was never, like, into high-tech stuff. I always really liked old school fifties movies—wacky, strange and funny stuff. And of course music, like punk rock and hip-hop and grunge that was coming out in the nineties while I was growing up. Skateboarding was my life. Every day, skateboarding, watching movies and stuff like that. I was bored with the people and my surroundings. I grew up pre-internet in a rural area of Skåne. Skating became my escape. We didn’t even have asphalt in the streets!

Then where did you skateboard?

People’s garages or at school. That became my school, in a way, always looking and searching and somehow find my spots.

i wanted to be a pro skater.

is that where the spatial awareness started?

Maybe, yeah. Since I was into this mishmash of culture, I wanted to turn my childhood bedroom into my own little world. I started to decorate it and maybe subconsciously that was a sign. People around me started seeing me as a creative person, but I didn’t see myself that way—after graduating, I wanted to be a pro skater.

what were the nineties in Sweden like?

My nineties were very much watching TV—when MTV came it was fucking amazing. I was, like, taping all those shows. 120 Minutes and Alternative Nation and of course Yo MTV Raps. I had my VCR ready to tape all the shows that I loved.

What was your childhood bedroom like?

I always loved playing with action figures and would build small worlds for them. Then, of course, I had Nirvana posters all over. I wanted the feeling of outer space. I started mixing antiques with found objects, like a dragon sculpture from someone’s trip to Thailand with a futuristic lamp. Lava lamps and stuff like that. A mix of strange things, like seashells that I collected.

What was it like getting into school and having to adhere to a practice?

I could never concentrate on anything growing up. School was extremely boring to me and I would always dream of other places to be. It was just a struggle. But cabinetry was the first time I felt hyper-focused and I could zoom in on something. I got really passionate about it. Not that I had an extreme passion to push boundaries, more an intuitive process and respect for the craft. I wanted to learn.

What did you start out making?

Like carving spoons and stuff like that. First it was basic, getting to know wood as a material, which at the time was new to me. The first assignment was making a stool, a classic thing, right? I’ve kept that stool at my mom’s place and I saw it the other day and it’s actually really close to what I’m doing now.

a good chair—don’t quote me on this—gives me as much pleasure as a good song.

would you say that form, rather than function, is what gives an object meaning?

Oh yeah! A hundred per cent. An interesting chair, don’t quote me on this, gives me as much pleasure as a good song, movie or book.

Why chairs?

Many reasons. It has one function, which is sitting, nothing else, pure function. It’s easy to tell if a chair is different from another chair, and whether it looks interesting somehow and if it’s comfortable.

How important is comfort to you?

It depends, comfort is one function, but not the only function. Like this one chair that I have which is this old Irish thing. The seat is really low and the back tall. You can just tell it was used for something special. Put it next to other chairs around a table and it doesn’t work! It has a specific function, but I don’t know what. I’m like a fly drawn to a piece of shit with that one, I’m drawn to it.

What does materiality mean to you?

There’s beauty in fancy materials but in my own practice I want to use simple and cheap materials, which have a value, but aren’t precious.

Do you have a favourite material to work with?

Pine, because it’s abundant. It’s easy to get a hold of and it’s soft. It has a pattern that almost makes it wild in a way. It has an interactive quality to it that I think is very interesting.

what else?

Anything that’s easily available. I only work with crap materials in a way. A lot of my work is about using what’s around me and then make it glow or vibrate somehow.

Tell us about that!

By using colour in different ways, like psychedelic and fluid colour combinations, I always try to create a sense of light. I love all sorts of colours, but when you put them together they have to create tension and feel luminous.

The psychedelic element, is it a conscious thing or a subconscious energy that you’re attempting to bring to the work?

It started out as a literal thing. Being fascinated by light phenomenas like nebulas and northern lights. Then when I was looking at the grain in the wood it also looks like a psychedelic pattern. By adding floating colours to it you’ll never look at wood the same again.

i love all sorts of colours.

How did you come to treat wood that way?

I had a clear vision of how I wanted it to look but actually achieving the end result turned out to be really tricky. I spent a year—my last year at the RCA in London—developing that technique by mixing my own stains. I tried all these different processes and just couldn’t get it right and almost gave up.

what was that like, knowing where you wanted to go but not knowing how to get there?

It was a transformation from what I had been doing. After cabinet making school I moved to Stockholm to attend Beckmans. I knew I had the skills in the craft, but didn’t know the design element. I spent my time there talking to all the students and I was really into the conceptual fashion of the moment—Margiela painting everything white—the anti-design movement, using standard fonts but using them in an elevated context. I was making simple furniture and painting everything white with a brush to take the attention away from the material. I was so fed up and bored by the cool and sleek Nordic design. I couldn’t relate to it at all. By making really simple stuff and painting it white, the design and shape could be the essence. That was the starting point. ¶ Then later at the RCA it was very experimental. The atmosphere there was right, but also very challenging—the criticism was very harsh. One teacher even told me that anyone could do what I was doing, which was sort of the point. Then I started experimenting with colours but I came to a dead end when I couldn’t achieve what I wanted. Then one night I was at a party and there were these beautiful, colourful garlands hanging from the ceiling and they fell down and got soaked, so they started dropping pigment and it was impossible to get the stains out from the wooden tops. And I think that it is my practice now, to dig where I stand. And it was that simple, I started using garlands.

So your work is just a party!

Totally! Everything was process-based design back then but this was so simple that I was ashamed to admit it. The story I was telling everyone was only about the early experiments.

Meanwhile this was your Newton moment, the apple fell on your head.

Haha, yeah. But then I realised that after a year that the colour fades, which wasn’t intentional. Now I make my own colours using pigments to mimick the simplicity of the garlands.

i was so bored by the cool and sleek nordic design.

Where are you now in your practice?

I’m in a sweet spot at the moment, balancing Joy Objects—a furniture company that I started with three friends. Joy has become my space to create things that people can bring home. My personal work has always had a functional element, but Joy has an even clearer mission statement: “Everyday objects for everyday use”. It might sound like a no-brainer, but for me it was a revelation: creating chairs that are affordable and accessible, without compromising on design, and creating a brand around it that still feels like me. I’m super proud of that.

What’s the best thing you’ve ever made?

It must be the Joy chair. It’s the essence of everything I’ve been doing. It’s so direct and straightforward, but it also has something else to it. In a way it’s like a sandwich, with different ingredients, materials and colours, so it can keep evolving. It’s also becoming a system, so it can transform to other pieces of furniture, like tables, stools, benches and storage units.

For someone who makes objects for the home, what is home for you?

It’s a safe zone, somewhere to be private. Where you don’t care about anyone else.

what do you do to relax?

I cook food. All types of stuff, nothing fancy. I enjoy doing everyday tasks, like doing dishes—all the things you feel like you have to do.

That’s actually a happiness practice, maybe you’re just good at finding joy! What kind of spaces do you feel more at home in?

The first one is called Glada Hörnan, my local pizzeria—“Joy Corner”—that place is amazing. And then this Colombian cafe called Kaffe Express Colombia.

How did you and Bodil meet?

Yeah, I’m noticing a fatigue almost. People are longing to do their own creative projects, outside of the feed. A year ago I had a period of feeling like an imposter and wanting to give up everything to become a baker.

i couldn’t do what i do without bodil.

Where do the two of you connect?

We have the same type of humour. We laugh a lot. We have a lot of fun just hanging out together.

What is it like both being artists?

It’s great, we talk a lot about our projects. I couldn’t do what I do now without her. There’s a constant dialogue. We talk about work all the time, but in a fun and challenging way.

what have you learned from bodil?

To allow for things to take time. I was so impatient before, still am, I was always rushing to the next project. Through her I learned to be meticulous and make the best out of something and really work out the details thoroughly.

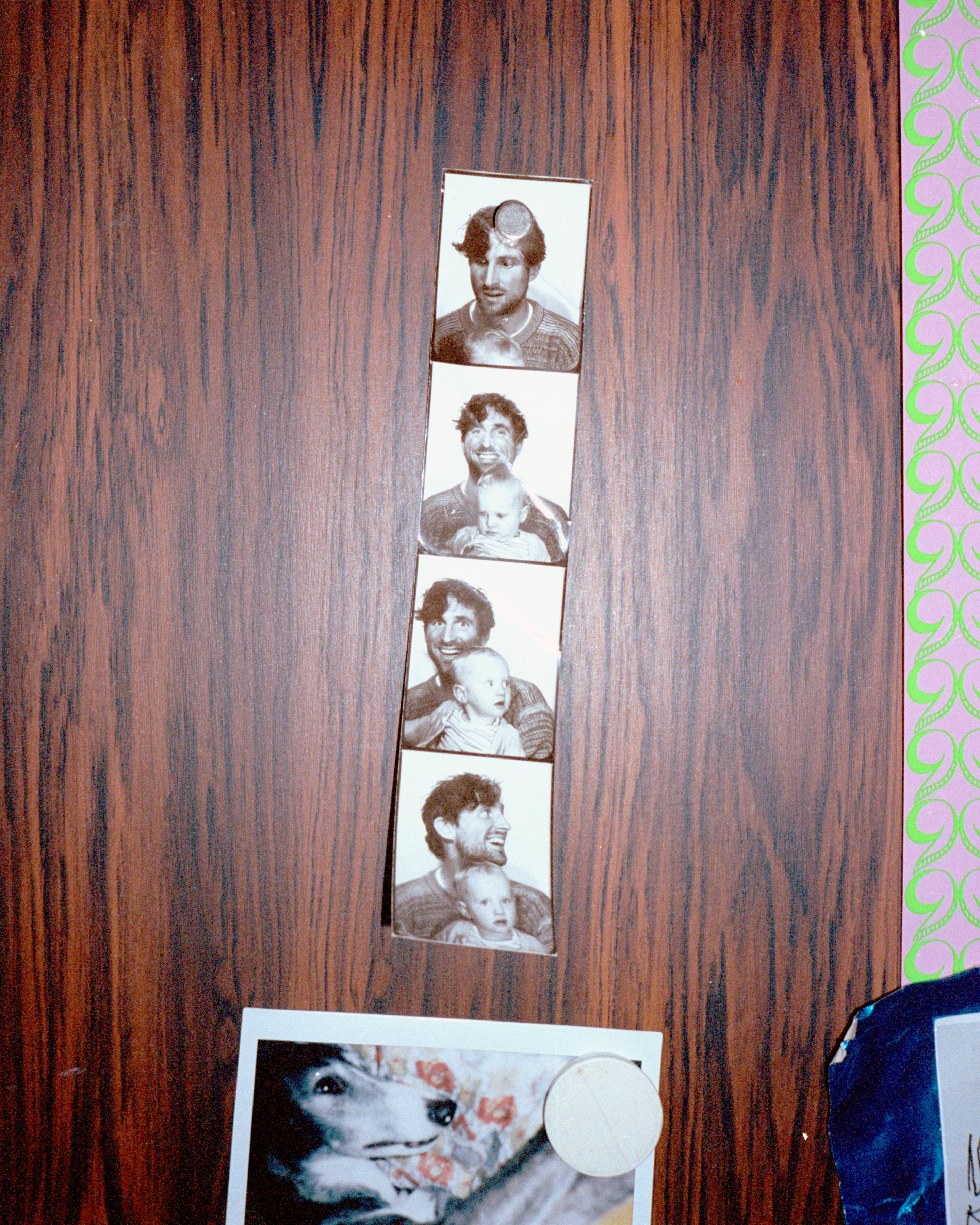

You also have a wonderful daughter, Karin, what has she inherited from each of you?

She has the worst morning mood, which I blame Bodil for. She’s incredibly creative, which I think she also got from Bodil, because I don’t feel like I’m creative. Bodil and Karin can sit and draw and make up stories together. I enjoy watching them.

dID YOUR identity change when you became a parent?

I don’t feel like I’ve changed. I’m still the same, but now I have a family. We listen to a lot of music together. She likes most of the stuff I like, like punk rock, heavy metal and rap. The music should be loud. Sometimes I wake up them with a song and she’ll ask me what song it is, asking who it’s by, really listening.

if your home was a song, what would it be?

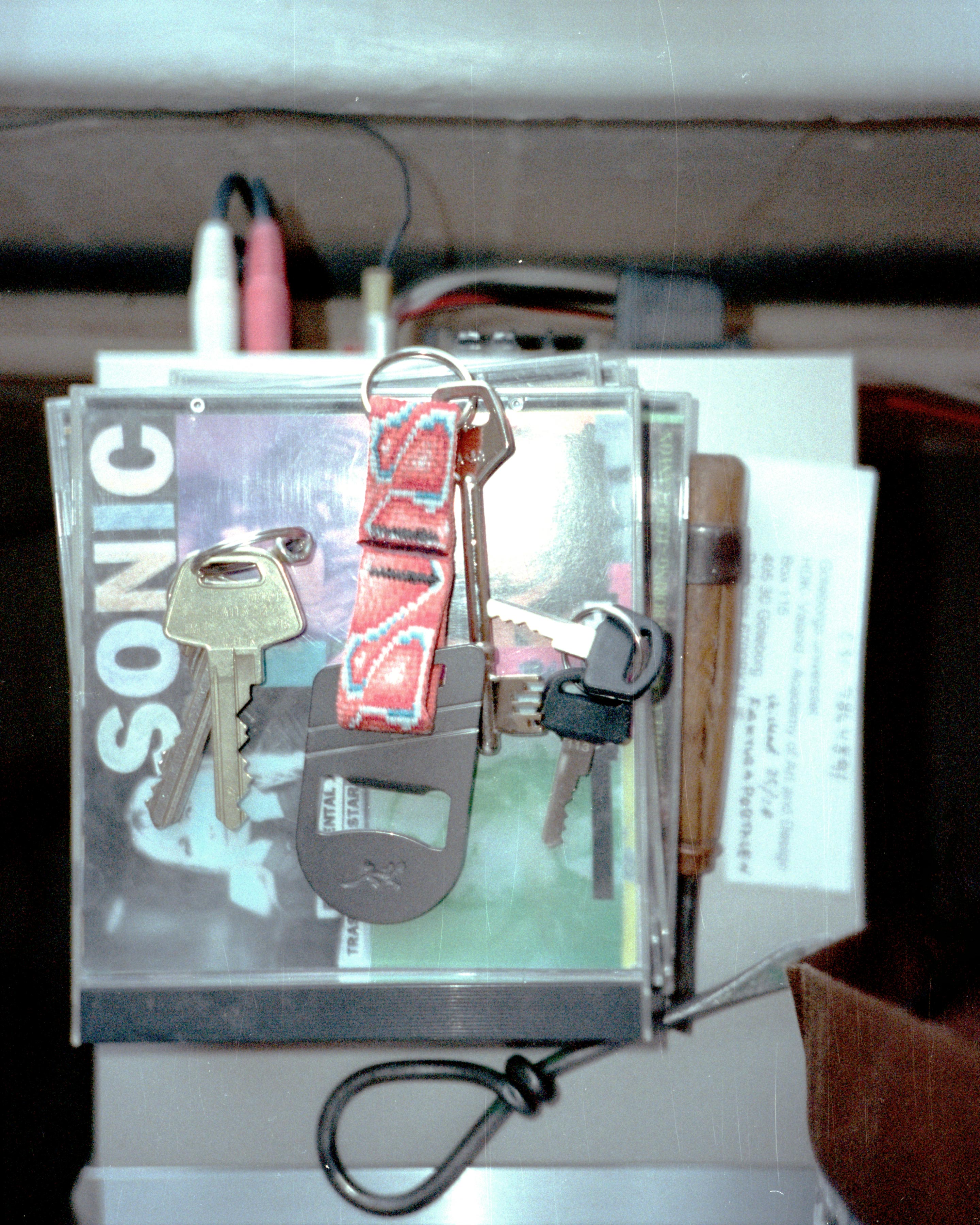

Probably The Diamond Sea by Sonic Youth!

weird, strange and cute at the same time.

what’s your most prized possession?

This exhibition catalogue from a Peter Shire show. He made a really nice drawing and dedication in it for me. It means a lot to me. But actually, my favourite thing by far is this tiny ceramic thing that looks like a horse to me, but Karin, my daughter, claims it’s a camel. It’s decorated with flowers. It has a container on the top. It looks like an ancient incense holder. It looks weird, strange and cute at the same time. That might have been my dearest thing until it broke. But I kept the scraps.

have you ever found any treasures by any good designers?

Twice, they were both by chance. The first was my Ettore Sottsass table that I found at Myrorna in Ropsten. They had it as a display table and had covered it with a table cloth and a bunch of glassware. I also found an Axel Einar Hjorth piece—this was way before the hype—immediately when I saw it I noticed how geometric, clean and brutal it was. It looked like something a farmer had made out of necessity. It was just so obvious, in a way.

you work internationally, but primarily in Sweden and Denmark, what are the biggest difference in terms of design practice?

Danes love culture and are very proud of their design legacy.Whereas in Sweden we don’t have that many masters to dictate the work. But it’s hard to create work in Sweden, because it almost feels like culture is despised here. For me design is culture, but the economy and mindset in Sweden holds it back by only considering the numbers.

What about the law of jante? Swedes tend to loathe anything that stands out, is that something you’ve been impacted by?

When someone is trying to do something new, people are very critical of it. Like “yes that looks good, but can you sit on it?” That’s why it’s so important to me to try and make stuff that is very personal, but stiill well constructed and durable. I just want them to say it’s a great fucking chair! ✿

i just want them to say it’s a great fucking chair!